My Research

I seek to understand how planets form and evolve, from their beginnings in the protoplanetary disk to their long-term atmospheric compositions. I am particularly interested in how traditionally separate aspects of planetary science, like interior evolution, atmospheric chemistry, mass loss, and disk processes, interact and influence each other. These days I mostly focus on super-Earths and sub-Neptunes. These planets, with sizes in between Earth and Neptune, are the most common type of exoplanet yet discovered, but their formation, interiors, and surface conditions remain mysterious. Read on for a summary of the work I've done in the field, or jump directly to my work on magma-atmosphere interactions in sub-Neptunes, atmospheric escape processes, or the work I conducted pre-graduate school.

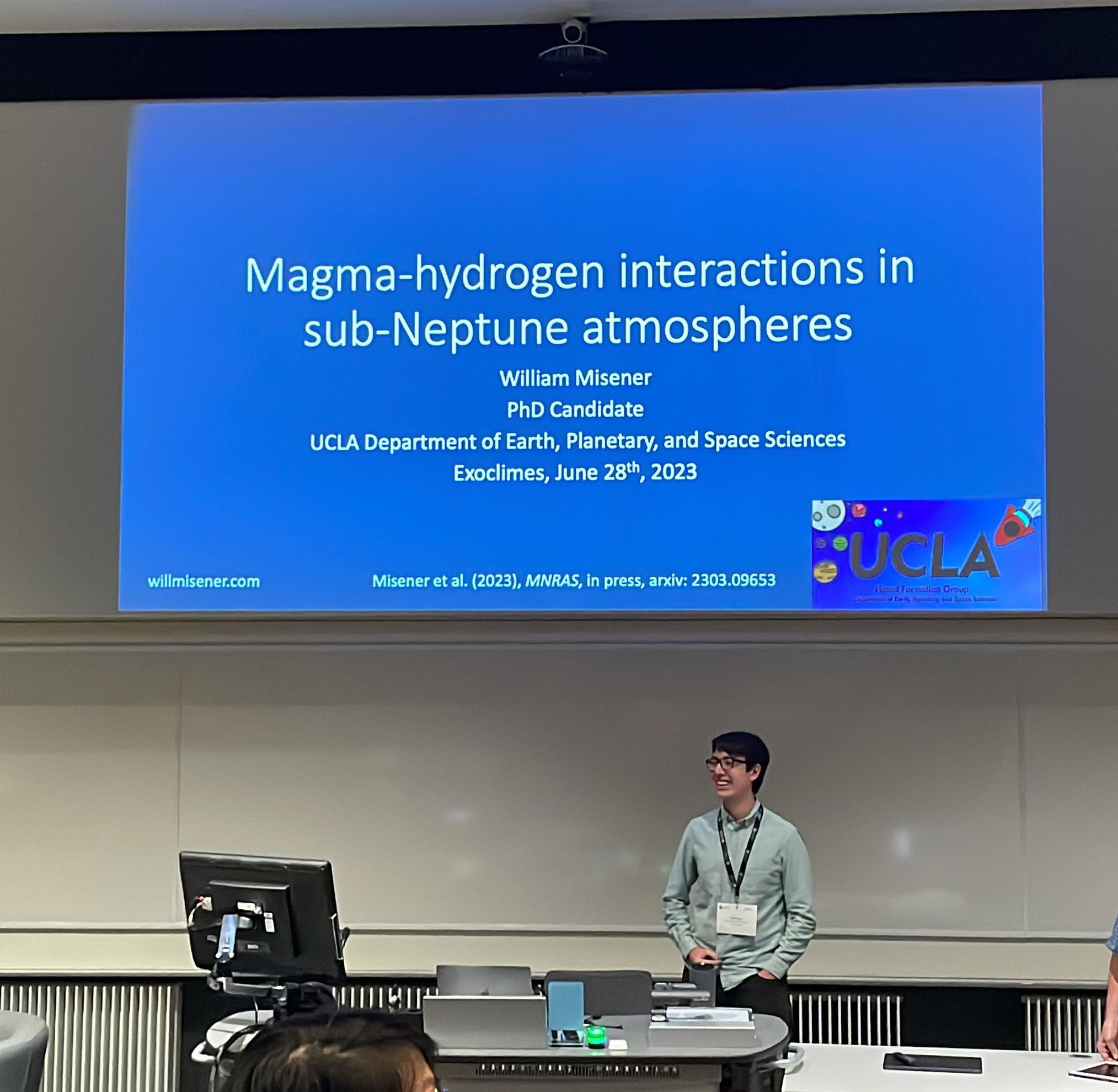

Magma-atmosphere interactions in sub-Neptunes

Many sub-Neptunes are suspected to consist of large silicate cores surrounded by thick hydrogen envelopes a few percent of their total mass. The atmosphere-interior interface of these surfaces should maintain temperatures above the melting point of rock for billions of years. Much of my research focuses on the implications of these long-lived magma oceans and their interaction with the hydrogen atmosphere.

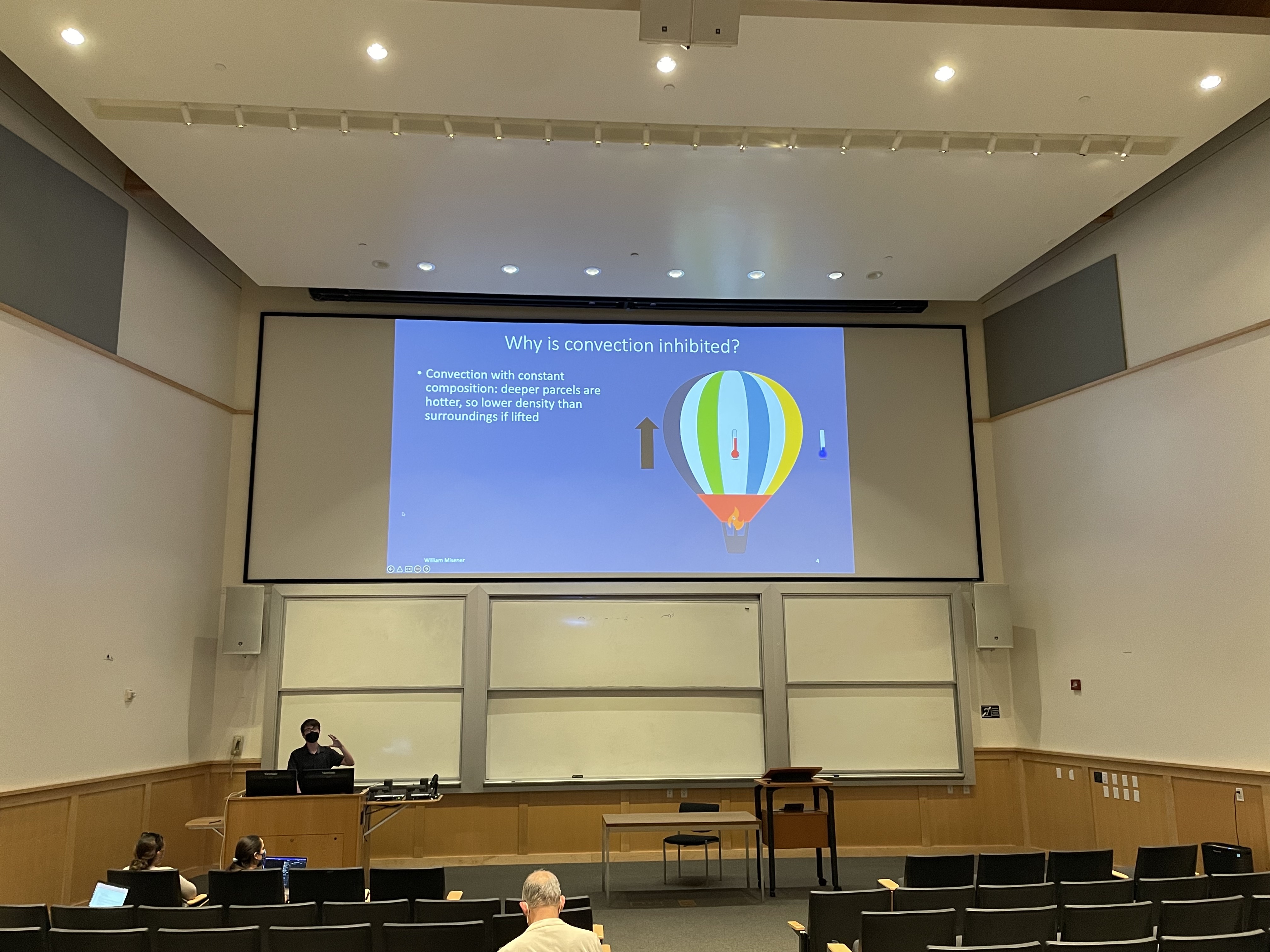

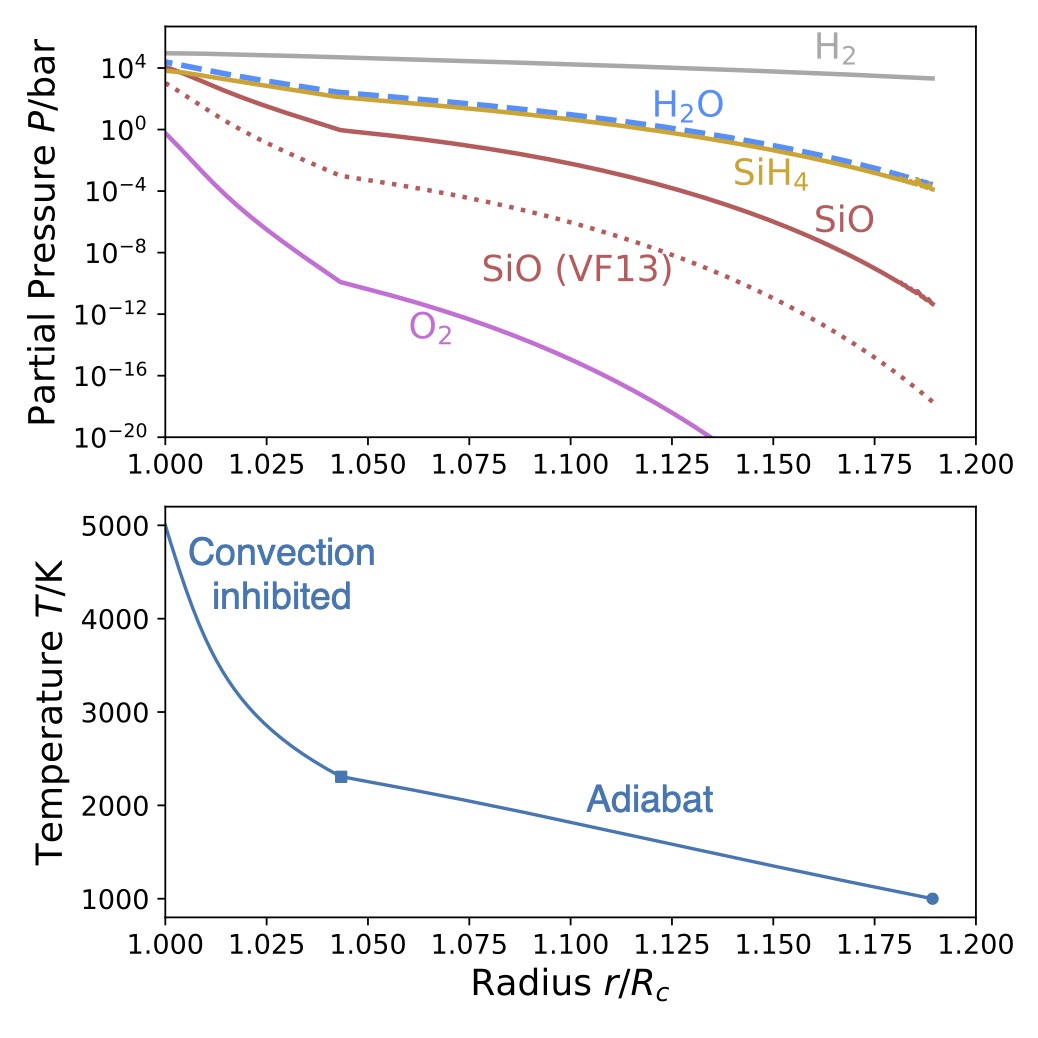

In Misener & Schlichting (2022), I show that silicate vapor, expected to be present in abundance at the base of young, H-rich sub-Neptune atmospheres, can inhibit convection. This inhibition is due to the mean molecular weight gradient formed by the condensable silicate vapor, which increases in abundance with increasing temperature. The resultant near-surface radiative layer can have a steep temperature gradient. This steep interior gradient decreases the width of the atmosphere, making it appear smaller than a fully convective atmosphere of the same atmospheric mass. Our work implies that the atmospheric mass fractions of sub-Neptunes inferred from fully convective models may be too low by a factor of five, and the effects can persist for billions of years.

I followed this work up with Misener, Schlichting, & Young (2023), which examines the chemical equilibrium expected in these atmospheres. We find that silicate species react with the background hydrogen to produce silane (SiH4) and water. The abundances of these chemical products of magma-atmosphere interactions decline with altitude, inhibiting convection over an even wider range of temperatures than we found in our 2022 work. This work shows that water is a natural product of magma-atmosphere interactions in sub-Neptunes. It also indicates that silane could be an observable product of sub-Neptune interiors.

Atmospheric escape from small exoplanets

Atmospheric escape through hydrodynamic winds is thought to be an important process in shaping small planet atmospheres and demographics. Two mechanisms have been proposed which both explain the observations, necessitating further theoretical investigation. One is photoevaporation, in which UV radiation from the host star drives a hot, fast wind. The other core-powered mass loss, in which the bolometric light from the host star drives a slower wind heated to the equilibrium temperature. This slower wind is still able to effectively remove hydrogen atmospheres because the silicate core cools into the atmosphere, keeping it inflated. I have led work examining various aspects of these two predominant mass loss theories.

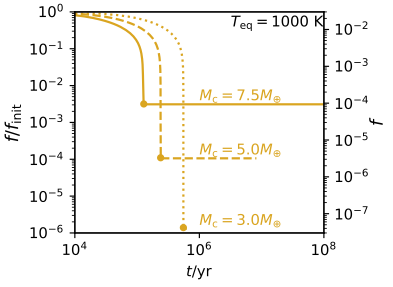

In Misener & Schlichting (2021), we showed that at the end of core-powered mass loss, super-Earth cores are able to cool faster than their atmospheres lose mass. This cooling allows the atmospheres to contract and preserve any remaining primordial gas. These findings imply that super-Earths that form via atmospheric stripping may retain hydrogen gas, which could affect the long-term surface chemistry and habitability of this common class of exoplanet.

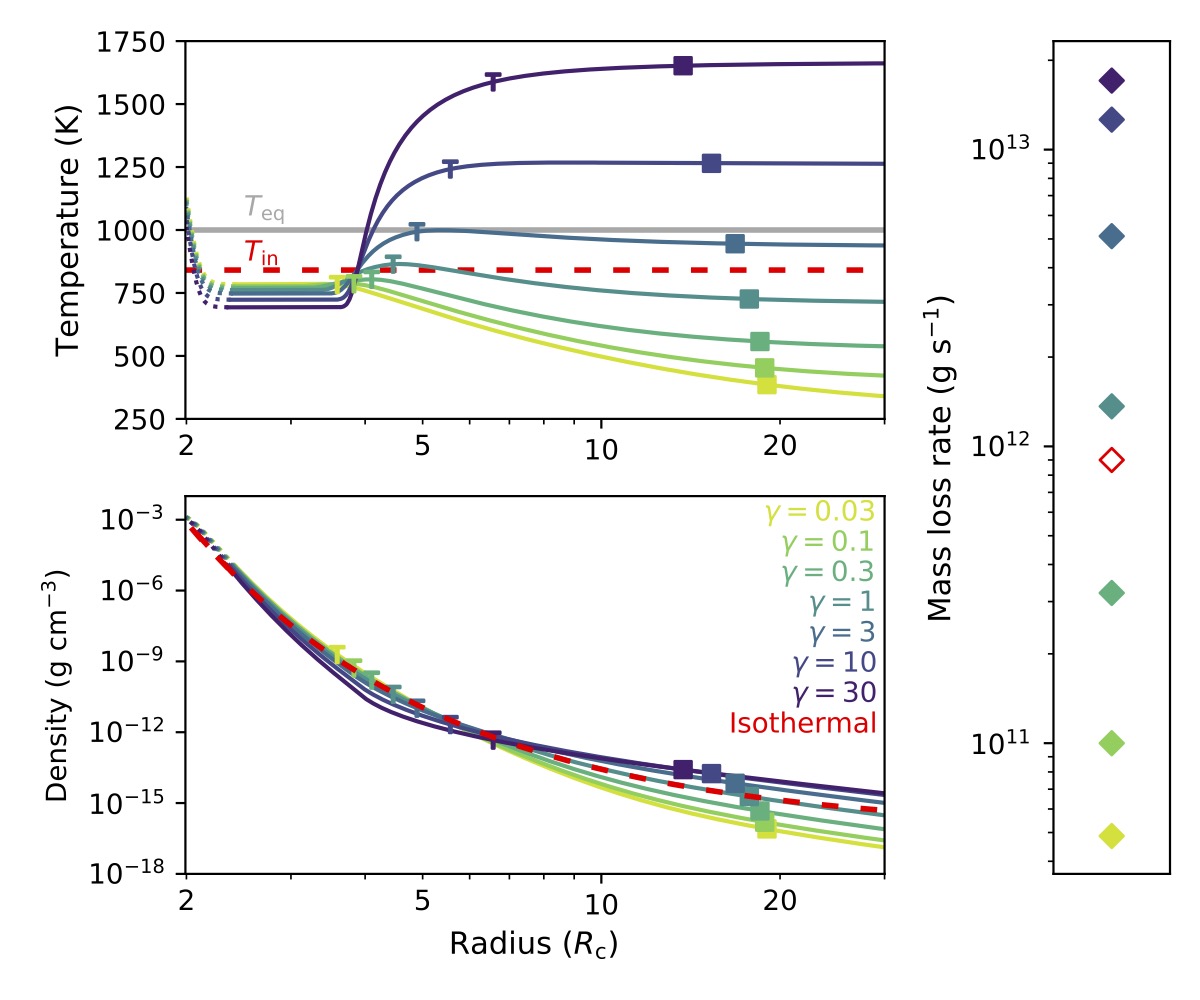

In Misener et al. (2025), we used aiolos, a 1D hydrodynamic radiative transfer code, to simulate core-powered mass loss with a hydrodynamic code for the first time. Previously, core-powered mass loss was modelled analytically. We showed that the atmospheric composition plays a major role in determining whether a planet can retain a hydrogen-rich atmosphere. Specifically, the relative opacity of the atmosphere in the infrared and visible bands determines the temperature in the stratosphere, which can change the mass loss rates by orders of magnitude. In some cases, the opacity in the uppper atmosphere can make the difference between a planet retaining or losing its natal hydrogen. Ongoing work will demonstrate how this effect alters planets undergoing photoevaporation, and elucidate the transition between core-powered and photoevaporative escape.

Bonus: read a science-fiction short story based on these hydrogen atmospheres written by Daniel Bensen, beginning on p. 18 here. This partnership was organized by the Exoplanet Demographics conference in 2020.

Work Previous to Graduate School

Dust Grain Growth and Transport in Protoplanetary Disks

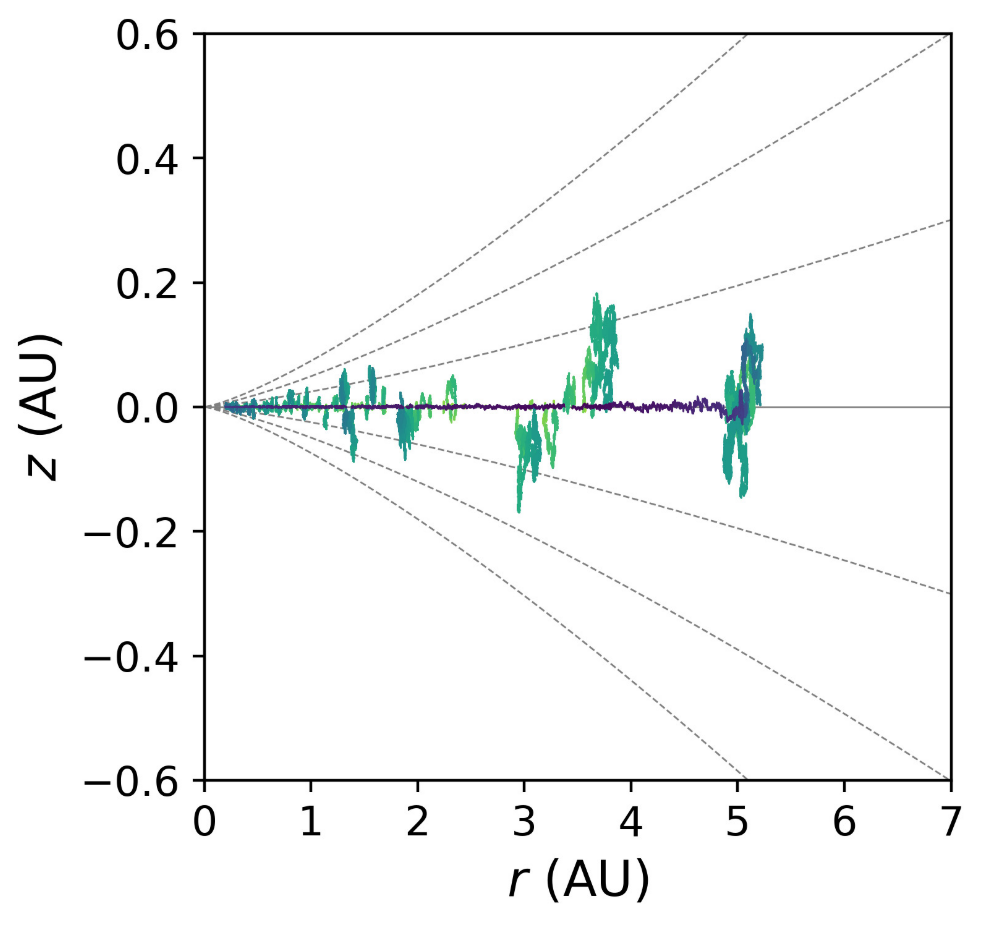

In Misener, Krijt & Ciesla (2019), I constructed a novel model for tracking the coupled growth and transport of individual small dust grains in protoplanetary disks. This model allows study of the diverse environments an individual grain encounters in the early stages of planet formation, while reproducing overall population trends. The collisional properties of dust, which dictate how it grows or erodes in time, and the movement of material through the disk are deeply linked, so it's important to model the two processes together. We found that diffusion alone is ineffective at transporting solid material outward, as the particles grow too fast. This growth leads to inward drift due to increasing drag from the gas. Mixing of material of different origins into the same body is much more effective if growth is limited by fragmentation rather than bouncing. This publication resulted from working with Professor Fred Ciesla and Dr. Sebastiaan Krijt at the University of Chicago as a Research Assistant for my junior and senior years of undergrad. This was also the topic of my honors Physics thesis.

Crater Counts on Mars

While an undergrad, I also participated in crater counting in the lab of Professor Edwin Kite. Crater counts are one of the only remote methods of dating the surfaces of other planets, but the counts themselves are time-consuming and usually requires significant expertise. My counts were part of an effort to produce expert-level crater counts by aggregating the efforts of a number of undergraduate researchers, whose time is relatively cheap. The results were published in Kite & Mayer (2017).